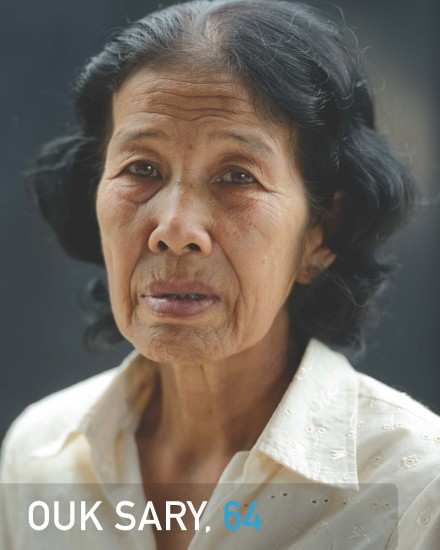

OUK Sary’s Testimony

‘I think about all this very often, every day. I still am in pain on the inside and I feel anger towards the Khmer Rouge. I am still wondering why they did such cruel things to their own people.’

My name is Ouk Sary and I was born in 1950. I am 64 and a widow. I work at home as a seller. My father’s name was Ouk Saly. He was a government official [before the Civil War]. My family owned houses and land both in Phnom Penh and Siem Reap, but we preferred to live in Phnom Penh as it was easier for us to go to school. I am the third daughter amongst nine siblings. All of us were born in Phnom Penh. All my siblings received higher education, but I dropped out of school in grade 3 of Boeng Keng Kang High School. Later, in 1968, I lived with my mother and six of my siblings in Siem Reap, separately from my father and one of my brothers, who were living in Phnom Penh. We communicated with each other very often. In 1974, I started working as a finance officer in the US embassy based in Siem Reap, so I even had a salary and was able to support myself and my family. In 1975, the Khmer Rouge came and took over the country and forcibly deported people everywhere. At that time, it did not matter if you belonged to the high class or low class – we all experienced the same things, such as the family being split up and being left in tears when we had to say goodbye to each other.

One day, when I left work and was on my way home, there were two Khmer Rouge cadres in black clothes bearing arms. They fired shots into the air and shouted at me to leave the house. My mother begged them to not take me, but they refused. I could not think about any mistake I could possibly have made.(1) I could only cry and think about being killed. I was forced by the Khmer Rouge to walk while my hands were tied together. My legs became very tired and I could hardly move forward. I was in fear and felt lost. My head felt so heavy and almost exploded. I realized that I was arrested to be one of their hostages in the forest in Domrei Chloung village or Koun Domrei village, Sva Leu district, in Siem Reap province. I witnessed so many people – children, men and women – being treated badly. They couldn’t talk, but just looked at each other. I thought that I might be considered to be part of the ‘New People’ (2) and that I might receive a different type of harsh treatment. I assumed that all those prisoners were New People who had been arrested by the Khmer Rouge. I was tied to a wooden pillar while other prisoners were standing or lying on the ground. Some of them cried and were bleeding all over their bodies. The Khmer Rouge cadres threw a small piece of potato at me to eat. I tried hard to swallow it, but I had to ask for water and they refused it. Even when we had to urinate, they did not untie us. A gun was pointed at many of the prisoners almost all the time. They forced me to overwork, both day and night, in order to complete their goal. Sometimes I was asked to pick grass or work in the rice field. Was I in hell?

I was slapped and kicked while being questioned four to five times per day to make me confess that I was a US spy from the Siem Reap base. I told them that I was not, and they slapped my head back and forth until I became dizzy and lost consciousness. I was told that one of the Khmer Rouge cadres knew about my family background, but I kept telling them that we were not US spies. They asked me if I could read and I responded, ‘No, I cannot read.’ They beat me up because they knew very well that I worked at the US embassy in Siem Reap province. I lost consciousness again. They brought water and poured it on my face to wake me up. I was tortured like this for ten days. I was very lucky that there was a man who came and confirmed that I was innocent so that I could be released. The Khmer Rouge leader released me, but I still did not have any rights. I was always dreaming and thinking of my mother and wondered where my family members were, but I could not get any information about them. I tried hard to live with them [the Khmer Rouge cadres] but it felt as if my chest was about to explode. The man who helped me get out of prison asked Angkar (3) and me to marry him, but I refused because I had not found my family yet. So I just worked wherever I was ordered to do so by the Khmer Rouge.

In 1976, I received good news about my mother and my siblings: they were still alive and had been deported to Phnum Bouk Kang Leach, Va Rin district, in Siem Reap province. That was near Doum Dek, Soth Nikom district, where I had stayed during that time. I was so happy and asked for permission to visit my family but the Khmer Rouge cadres refused. I decided to escape and to look for my older sister, who lived in Va Rin district. Unfortunately, I was caught and sent back. I was imprisoned a second time, but this time, they did not severely beat me. However, it was not a happy time as I and other prisoners, who were considered to be New People, were forced to obey and work in accordance with the Khmer Rouge doctrine. We were imprisoned during the day and had to work at night carrying soil, farming or collecting grass, and so on.

We had no time to rest, no right to demand anything, but we worked really hard because we wanted to survive and be reunited with our families. Every day, we only saw the forest and the mountains. We witnessed the killing and torture of prisoners. Many children became sick and the Khmer Rouge threw them in the air and then bayoneted them. Many children, men and women were killed and the smell of the corpses was everywhere in the forest. That was the cruel history of the Khmer Rouge.

I and other prisoners had to stay there until 1978. After they released us, we could go back to our homes, but unfortunately some lost their lives in the camps. I was later informed about the death of my third older sister, my brother-in-law, and my sixth sister, as well as three of my nephews back in Va Rin village, Kouk Doung district, in Siem Reap province.

The worst news was about the death of my sixth sister. She was killed by the Khmer Rouge. Before she died, she was raped. They cut her vagina, cut her nipples. My mother heard about this and cried until she lost consciousness.

One month later, I found out that my father had also been killed by the Khmer Rouge. My second-oldest brother, as well as my fourth-youngest brother and his wife, were all killed in a Region 21, in Tonle Beth, Kok Sotin district, in Kampong Cham province.

I think about all this very often, every day. I still am in pain on the inside and I feel anger towards the Khmer Rouge. I am still wondering why they did such cruel things to their own people. Before they killed my father, how did they torture him? How much pain did he experience when it happened? I lost seven family members during the regime. Only I, my mother and six brothers and sisters survived the regime. We are still struggling almost every day to live with the pain and fear. My mother and I often have nightmares about our terrifying experiences and my mother still does not dare to talk about it. She prefers to remain silent. She struggles to survive with her pains and worries.

In 1981, with the agreement from my mother, I got married. My husband, whose name is Lao Chea, has Chinese blood. He is a seller. We lived together for twelve years and we had two lovely sons. My husband was a smart guy and he made good money. Unfortunately, in 1990, he was robbed and killed.

After that, I lived on my own as a widow and took care of my children. Remembering my husband’s will, as well as the Buddhist concept, I wish to live in peace and I wish the bad karma from this life to not be repeated. If I could have one more wish, it would be to remain hopeful and to insist that the Khmer Rouge Tribunal brings justice for the dead. As a Civil Party in Case 002 of the Tribunal, I won’t claim any reparations, but I wish to have peace and…

… I would like to dedicate this testimony to my loved ones, who are the following:

- My father Ouk Saly

- My older sister Ouk Saron and my brother-in-law Chea Pov as well as my three nephews

- My sixth-youngest sister Ouk Phana

- My second brother Ouk Sothy

- My husband Lao Chea

Please rest in peace and receive my respect. I wish that your souls live peacefully and that they will be reborn in the next life.

I also want to thank TPO for giving me the opportunity to have my testimony established today, and I would also like to thank the other organizations that are working in the context of the Tribunal, for being a role model and for seeking justice for the Cambodian people.

Testifier: Ouk Sary

TPO Counselor: Chhay Marideth

Notetaker: Maryna

Phnom Penh, 17 July 2013

_________________________

FOOTNOTES

1 She was thinking about which ‘mistake’ against the Khmer Rouge regime and their doctrine she could have made to cause her to be arrested by them, but she could not think of anything.

2 People moved by the Khmer Rouge from the cities were called ‘New People’ and were viewed as enemies of the regime. ‘Old People’ (also called ‘Base People’) were those who were living in the Khmer Rouge’s ‘liberated’ zones before 17 April 1975. They were more trusted by the Khmer Rouge.

3 The CPK (Communist Party of Kampuchea) referred to itself as ‘Angkar’ which is the Khmer word for ‘Organization’.